A century ago, the old Red River Pass helped transform a dying mining village into a popular summer destination

Late winter. The wind howls through the valley, whistling through abandoned miner’s shacks and boarded-up storefronts. Except for smoke rising from the occasional chimney, the place looks deserted. The boom had come and gone. Though 3,000 people had lived and worked around the ambitiously-named Red River City in 1897, by 1914, there remained only several dozen hardy souls; miners who still dreamed of the motherlode, homesteaders up to the challenges of Alpine life and those who simply loved the place and never left.

As the author Bill Divin called it, “Empire of High Hopes,” dreams of vast mineral wealth had never panned out, literally or figuratively. Placer gold (the kind found in streams) was depleted early on. Other ores proved to be low-grade and poor transportation made taking material elsewhere for processing unprofitable. Talk in 1906 of a railroad into the Moreno Valley and on to Taos went nowhere, and no rail connection ever came closer than Ute Park.

The road to that connection was also downright frightening. Following the natural pass over Red River Hill from Elizabethtown through Road Canyon, the unimproved path was so steep, travelers would cut down a tree at the top, tie the log to their wagons and drag it behind to stop them from running over their own horses on the way down. With grades up to 27 percent, the road was treacherous when dry, prone to washouts, and impassable to wagons in the winter.

So that March, in 1914, the people of Red River met for the second time to discuss building a new road. Organizing the first meeting the previous November was the work of Norman L. Faris. The Iowa-born Colorado mining engineer had been working near Ute Park and only recently arrived in Red River, but his enthusiasm for the area’s potential was so infectious that he convinced the locals there was no future in Red River without a new roadway.

A Good Roads Association was formed at that second meeting, with Sylvester Mallette, Caribel mine-owner H.L. Pratt, and Faris as officers. Faris did much of the legwork, traveling the state to secure funding. The State Legislature was tapped out from financing the Camino Real project. Taos County was building a new highway to the Colorado state border (old State Road 3) and could only provide $750 — and only if the people of Red River raised the rest. Finally, the U.S. Forest Service agreed to take on the project.

An initial survey was conducted in August and on Sept. 10, a crew led by engineer Howard B. Waha arrived to finish the job. The new highway had several requirements to meet Forest Service standards: maximum grades of 7.5 percent on straightaways, lowering to 3 percent on switchbacks; a minimum radius of 36 feet around switchbacks; location on a southern slope to reduce snow accumulation; and pull outs every 700 feet to allow cars to pass. Culverts and drainage also had to meet stringent standards.

Work began in June 1915. As per Forest Service policy, most of the workers were recruited locally, with men coming from as far as Sunshine Valley and Taos to take part. The work was initially led by Howard Waha, but he returned East to marry his sweetheart and teach at Syracuse University. (Waha would later return to New Mexico and design sections of Route 66.) From August on, the work was supervised by Norman Faris and Waha’s assistant Kenneth C. Balcomb. The men managed to carve out a narrow path that year, allowing automobiles to safely enter Red River for the first time.

The project was completed the next summer under Balcomb’s supervision. Norman Faris returned to Colorado and joined the Army Engineers. He died in France on October 8, 1918.

While much of the first year’s work was done with horse and mule teams, most work the second year was done by hand, most notably by men from Taos Pueblo. Dynamite was used only on a limited basis, mostly at switchbacks and for removing stumps. Everything else was done with raw human and animal labor. Safer and easier to negotiate, the new road was considered a modern marvel.

While investors would keep promoting the mines, a new type of gold rush was starting. Reports of Red River’s cool summers and ample trout had been in magazines and newspapers as early as 1896. Tourists began pouring into Red River, even before the road was finished. Locals refurbished miner’s shacks to rent out and began building new accommodations at once. The quiet, isolated little burg quickly became a bustling destination, with summer populations to rival the boom days. The new pass also served as a gateway bringing tourists to Taos and Questa as well.

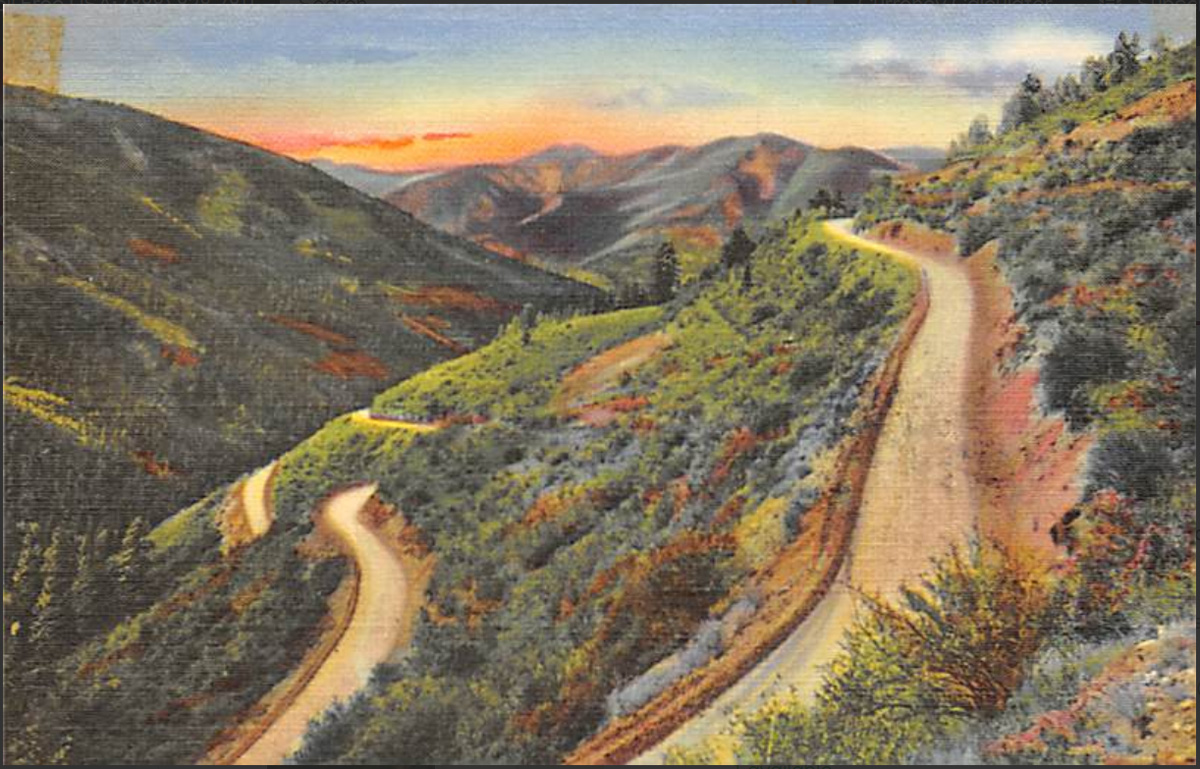

For the next several decades the Red River Pass continued to serve the town and region, helping the local economy survive the Great Depression, the end of mining in the early 1930s, and the lean years of World War II. Driving the Red River Pass was considered an attraction in itself, as each switchback revealed new breathtaking vistas of the valley. Views of and from the pass even featured on postcards.

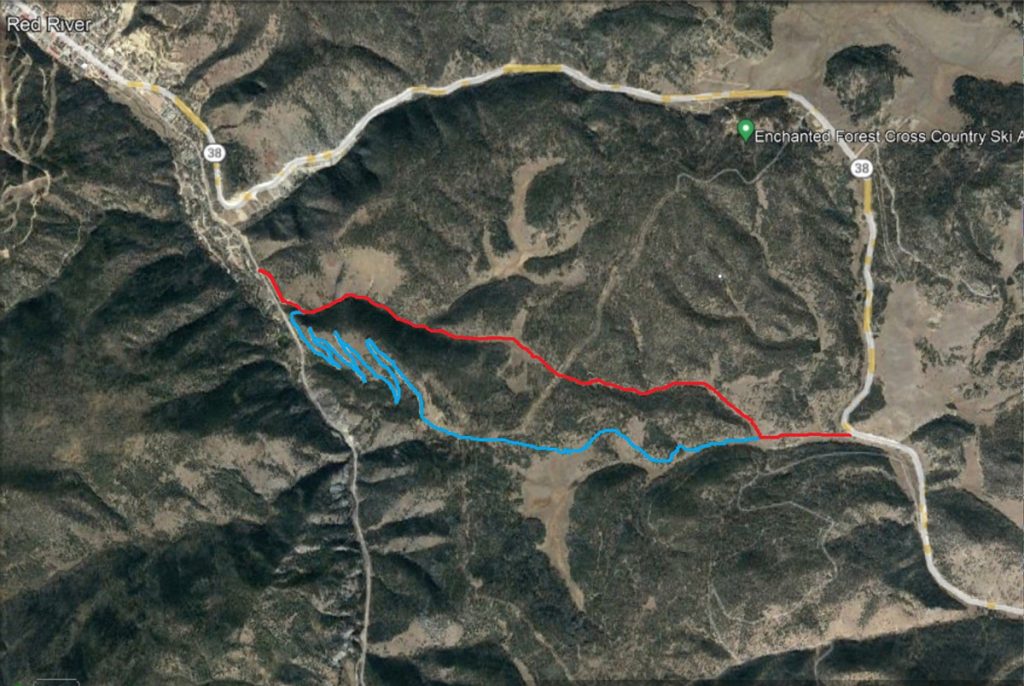

By the 1950s, the once modern marvel was feeling outdated. Many drivers accustomed to asphalt found it as frightening as their grandparents had found the original road. With the ski area opening in 1959 and the town’s new winter tourism, New Mexico Department of Transportation decided it was time for an update. Work began on a new road over Bobcat Pass in 1962 and was finished by the summer of 1966. The Red River Pass became “the Old Pass,” closed to traffic and gated at the Colfax County line.

The switchbacks became Forest Access Road 488 and found a new life as an off-roading and hiking trail. Today, the carvings on the aspens bear witness to the generations of locals and tourists who have made the trip up to see one of New Mexico’s most beautiful panoramas. The men who built Red River Pass would be proud to know their work remains, still helping people discover the beauty and wonder of this place we love.

https://fotogrande.com/last-days-in-the-empire-of-high-hopes/

Kenneth C. Balcomb’s book The Red River Hill provided the backbone of this article.

It provides a colorful firsthand account of the building of Red River Pass and of life in the valley in those years. It is available at the Little Red Schoolhouse Museum on Jayhawk Trail, Red River.