By Martha Shepp and many others

This community paper is endeavoring to offer a Questa mine history series over the next few issues, to bring you stories from the earliest discovery of molybdenum right up to the present with the goal to review, freshen up the facts, and celebrate the story of our place.

From Part III:

1979 Even though no molybdenum mines are producing in the US, only Molycorp embarks on a massive development effort in anticipation of better times. Operating costs are held constant and labor and supplies are kept under control. Through careful planning and an intensive training program, Molycorp avoided the layoffs often experienced between the phasing out of one mining project and startup of another. Employees are retrained: mechanics, mill operators, and laborers all became construction employees to rebuild the mill after it was closed in 1981.

Part IV

With the arrival of this new mining-based cash economy, people in Questa suddenly had a new way to make a living as miners. By the 1980s, the Moly Mine employed hundreds of people (about half from Questa and the other half from Taos County), but this was a boom-or-bust economy with work at the mine dependent on world markets for molybdenum.

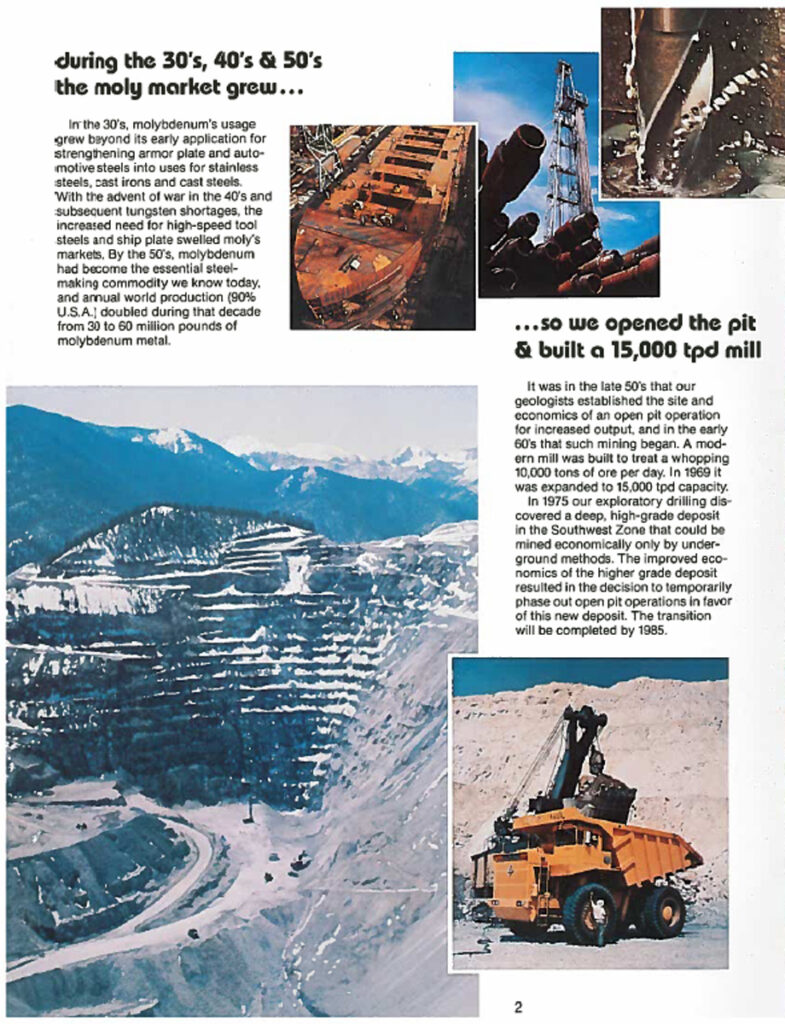

1983 The new $250 MM facility opens, in anticipation of better times that had not yet manifested. This method is mining up from below, instead of down from above. The ecological advantage to underground mining is that the decline naturally fills itself, while open pit mining denudes two areas—the strip itself and the place where waste rock is dumped. It was a bold move. The March 1983 issue of the New Mexico Business Journal (cover story) proclaimed in this headline “Molycorp risks $250,000,000…”

The new mine proved highly efficient, operating on the principle of “gravity block caving”: Tunnels were cut under the ore deposits, which were blasted out with explosives. The ore tumbled down “by gravity” through a series of excavated chutes to rail cars; it was then transferred up to the surface by conveyor belt and fed into the mill for processing. “This ultra-efficient moly mine and mill will allow us to become one of the nation’s lowest cost primary molybdenum producers,” said Tom Sleeman, president of Molycorp division of UNOCAL, at the time of its 1983 dedication. Efficient production was the key, since some of the company’s competitors produced molybdenum at a very low cost as a by-product of other mining operations. By the end of 1984, production was up to 12,000 tons. The markets, however, had begun to shrink in 1983 with dropping oil prices. Demand for steel was down, not just in the oil patch but for all industrial applications. The American steel industry in particular was in a devastating slump, suffering from over-capacity and inefficient methods of production.

1986 The mine’s first shut-down, following the collapse of oil prices and with the oil industry cutting back operations.

1989 Questa mine reopens with market improvements, employing 225 workers, with apparent improved market conditions. Production runs at about half annual capacity of 20 million pounds.

1990 Beyond the Questa mine, Molycorp discontinues its worldwide exploration of mineral. Prices continue to drop. Offices were closed in Australia, Brazil, Canada, and the US.

1991 The Questa mine is again shut down due to market conditions and this time, significantly, the mine workings are allowed to flood; Molycorp’s Washington plant roasting facilities are mothballed. The 225 workers were laid off.

1993 Molycorp’s York plant is closed and environmental cleanup commences.

Decades of mining have produced millions of tons of waste at mine sites, which the 1993 NM Mining Act addressed. The federal 1872 Mining Act was still in effect: few laws on the books display such largesse to industry. For so long, the public lands of the American West have been a welfare paradise for miners, oil and gas developers, loggers, and ranchers: lands to be exploited for easy profits. The purposes of the NM Mining Act include “promoting responsible utilization and reclamation of lands affected by exploration, mining or the extraction of minerals that are vital to the welfare of New Mexico.” The act establishes requirements for a broad range of “hard rock” mines to obtain permits, meet operation and reclamation standards, develop an approved reclamation plan, and post financial assurance to support the reclamation plan. Amigos Bravos’ 2005 actions gave the 1993 Act some teeth.

1995 The Mine started up again, with most of the year devoted to de-watering. Actual production began in late 1996.

1996-99 Limited production at Questa. Toxins from mining operations reportedly leaked into a nearby fresh water at another Molycorps facility, which spurred several government agencies in a “search and seizure” of all Molycorp records. Cleanup of the release material continued under the direction (either directly or indirectly) of 29 governmental agencies.

2000 Development work at the Questa mine continued with expectations of production by mid-year. Reserves of this orebody were estimated to provide for at least 15 years of production.

To be continued…

Fringe Benefits

In addition to providing employment and having a $120 million investment in the mine, Union Oil provided these services: clearing roads of snow in the winter and debris from heavy water flow in spring, and flash floods in summer. They also built a baseball diamond at Questa High School, water well drilled and deeded to the village of Questa, ambulance service for Questeños needing to go to Taos for medical care, and good TV reception because of an antenna erected atop Flag Mountain. In 1978, engineering skill, pipe and labor were provided for a water system supplying the Red River Hatchery.

We are proud of our relationship with northern New Mexico, and particularly with our host, the Village of Questa. Without their encouragement and cooperation, this mine couldn’t have become successful.

—C.R. “Bob” Sacrison, Questa division of Union Oil, 1983

Author

-

Questa Creative Council Board member and artist: Martha Shepp preaches the gospel of the power of creativity. One of her loves is to collaborate with open-minded genre-free artists like Mark Dudrow, playing life-affirming works that can’t help but spark the innate creativity of listeners like you. Her expressions also take form with words, choreography, and visual art... with ever expanding mashups of all the above.

View all posts