By Martha Shepp and many others

This community paper is endeavoring to offer a Questa mine history series over the next few issues, to bring you stories from mining’s earliest discovery right up to the present.

The landscape around Questa, Red River, and Taos, like many parts of the west, is marked by a cultural history of mining. When hiking, even in what are now protected Wilderness areas, it’s not uncommon to come across remnants of prospecting pits, mine shafts, or old mining equipment from early in the previous century.

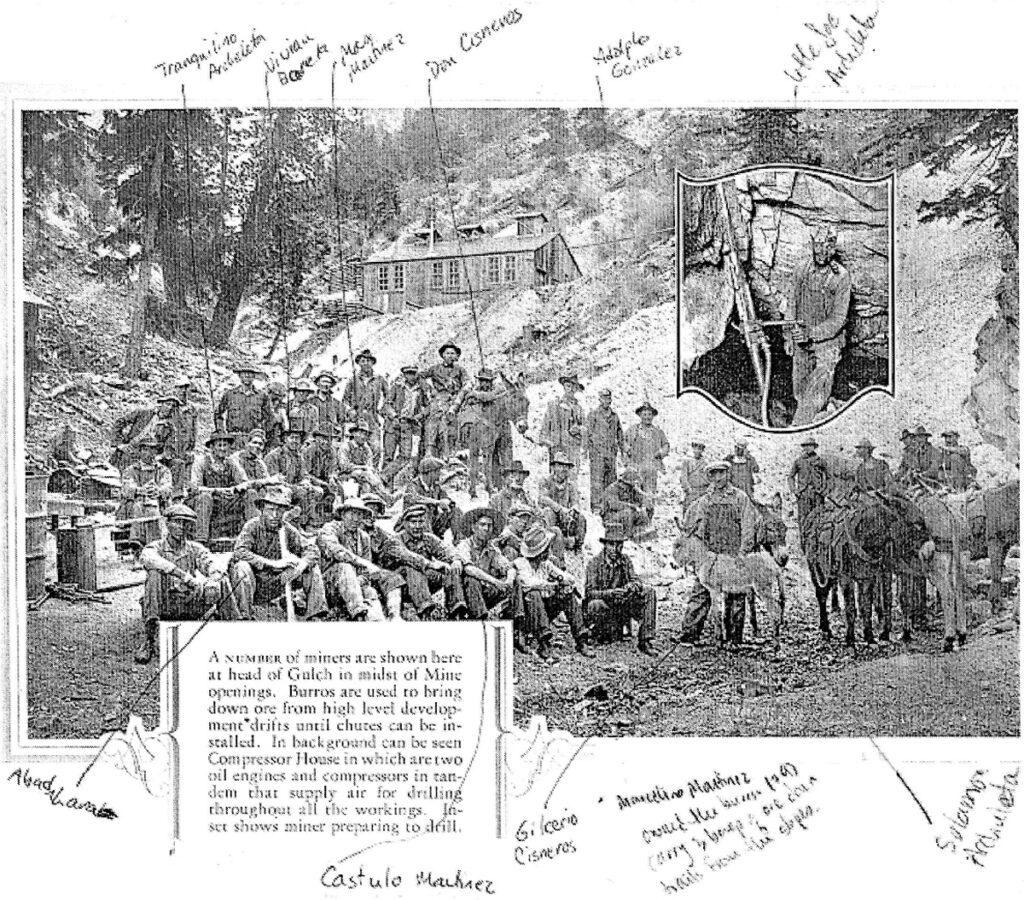

For a long time, the “Moly” Mine WAS Questa. Its other cultural, economic, and social aspects became pale background figures. The mine is in the timeline of Questa, for sure, in a big way. It grew to become the largest mine in the Rio Grande watershed and has over 100 years intertwined with Questa history. By 1926, it had become the second largest producer of molybdenum in the world (after the Climax mine in central Colorado): An amazing legacy!

In my experiences with community building, even from the time I was a teenager witnessing (and sometimes helping) my parents working with NGOs at the neighborhood level, I was continually impressed by the positivity and forward momentum resulting from a community that got to know their true history: the unique imprint that each place has—for ill or for good—and celebrating it.

The Questa History Trail accomplished this, and is a resource for any of us to view by walking the half-mile loop, or digging more deeply into the team’s research through the trail website. State and national historic archives are available for the digging, too; and our public library is beginning to put documents together, thanks to donations of research materials from Judith Cuddihy, co-author (with Tessie Rael y Ortega) of Questa history opus Another Time in this Place—online here. Who can Questa become in “post-mining” economy and culture? This is what the Questa Economic Development Fund (QEDF) and all of us aim to discover and nurture, new endeavors and talents, reviving old cultural pathways along the way, many that were perhaps too overshadowed by the mine’s prominence.

Back to the mine, though. This may be a good time to review, freshen up the facts, and celebrate the story of our place. I personally want to do the mine series because the “mine story” feels to me no longer alive. I heard: “It thrived, then it didn’t, then it closed”—this is just too simple. The complexity of interrelated stories, the history as it was lived by human beings; this is part of the mine story, too, and worth telling again… or for the first time.

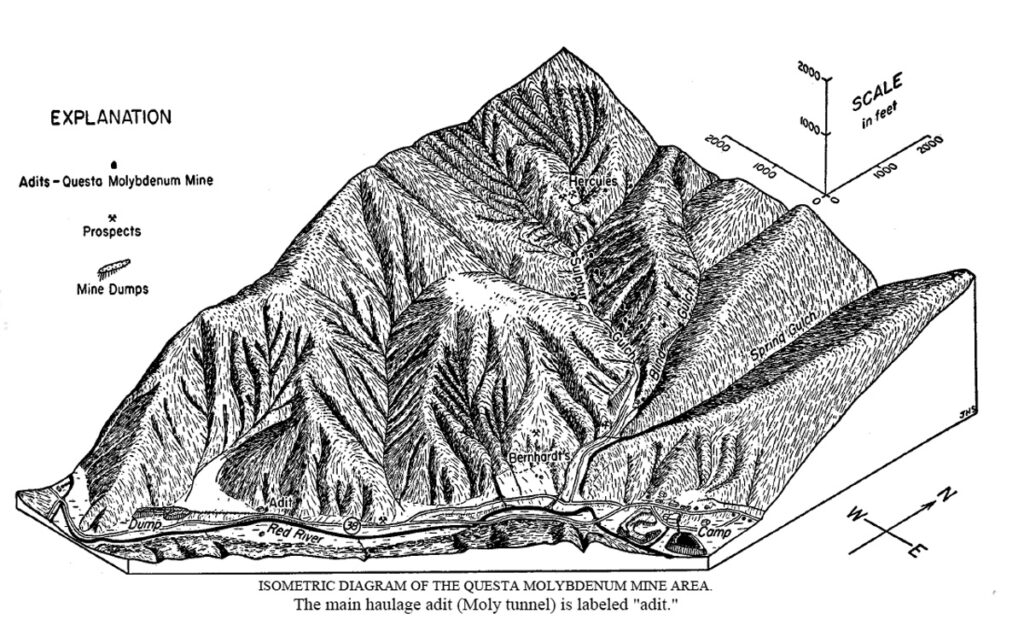

Molybdenum: The molybdenum deposit was formed in the Questa area, under Goat Hill as follows: In the Miocene epoch, 23 million years ago, igneous rocks intruded a weak, faulted zone near the southern part of the volcanic caldera area. The intruding rocks are granite and aplite porphyries; the overlying volcanics are andesites and rhyolites. After intrusion, hydrothermal fluids (wet and hot) boiled off the intrusive rocks and deposited molybdenite in fissures in the overlying volcanic host material, and in concentrations great enough to form many nearby deposits in the central and southern Rockies.

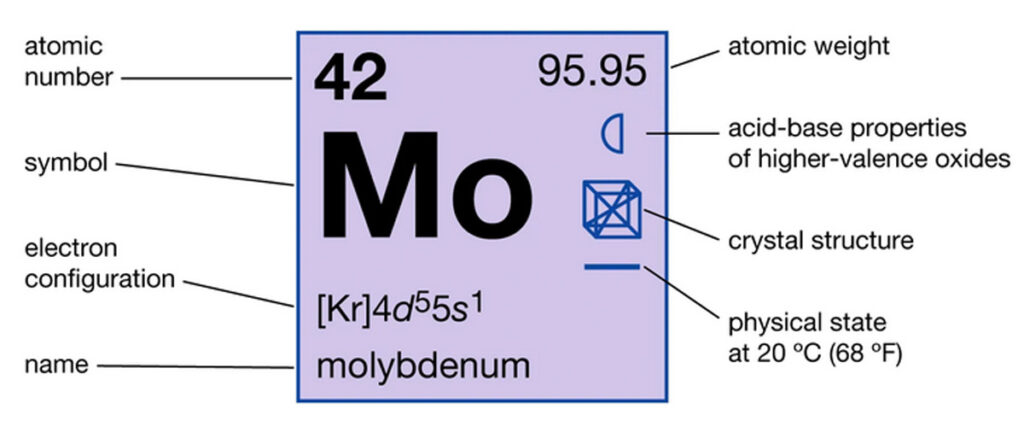

Molybdenum is defined as a “refractory metallic element used… as an alloying agent in steel, cast iron, and superalloys to enhance hardenability, strength, toughness, and wear and corrosion resistance.” It is not as black as charcoal and a bit softer than pencil lead, and is a replacement for tungsten with the advantage of being of lighter weight.

Ancient History of Questa

The Questa area has shown evidence of habitation from as early as the Paleo-Indian Clovis, then Folsom people. Around 5000 BC, as temperatures warmed, permanent settlements moved into our area following the movements of big game. Since then, however, the region lacked permanent settlements for many centuries, though the area remained a crossroads for hunting and trading between the Native Pueblo people (as the later Spanish speakers referred to them) to the south and the Plains nations to our north and east.

Seeking Precious Metal

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado may have been the first Spanish visitor to the area, traveling through in 1540. In 1592 or 1593, more Spanish came through, following rumors of gold. Reports tell us that many did not survive. The next century saw turmoil as newcomers attempted to settle in areas already important to Native Americans, and wealthier newcomers enslaved Natives to work in diverse roles, including as miners. This continued until the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 which cast the Spanish out of New Mexico (for a short time).

The search for gold and silver north of the Questa area continued to bring travelers through this area. In 1761, Governor Manuel Portillo explored San Luis Valley for minerals (39), and in 1768, the expedition of Don Juan Maria de Rivera traveled up from Santa Fe through the Chama River area and then back down through San Luis Valley. To protect their explorations and mineral finds, the Spanish built a fort on San Antonio Mountain in 1768.

Although settlements in this location were documented several different times in the early 1800s, new residents were vulnerable to deadly conflict for generations. Several times, all residents completely abandoned the area.

The Mining Act of 1872

President Ulysses Grant signed into law the General Mining Act, designed to give incentives to the then-budding mining industry to go west and create jobs and raw materials for a growing America. Prior to 1872, the miners themselves largely determined mining laws that had pre-existed in California. Miners would form governments in each new mining camp, which led to a lack of mining standards, violence, and little state or federal control. It also opened claims to include “other valuable deposits” beyond gold, silver, copper, or cinnabar.

Gold Rush Hits NM

The first Rio Colorado (one of Questa’s previous names) connection with the copper and gold rush in the Moreno Valley was William Kronig, who had lived and did business in Rio Colorado in the 1850s.

Moache Ute Indians had brought colored rocks to Kronig and Captain William Moore at Fort Union in 1866. Kronig and Moore sent several men to investigate the source of these rocks—Mt. Baldy—and they identified them as copper. Kissinger, Bronson, and Kelly were then sent with Ute guides to Mt. Baldy and while there, they discovered “gullies and creek beds” full of gold flakes—the secret couldn’t be kept and so the gold rush was on (186) by the spring of the following year, despite Moore’s desire to keep it secret.

Kronig, Moore, Lucien Maxwell, and others formed the Copper Mining Company and when work started in 1867, they found gold in large quantities. By the spring of 1868, over 3,000 people were working the gold fields and living in the new town, Elizabethtown, in the Moreno Valley. By 1899, about $3 million worth of gold had been mined in the Baldy area (187). A new town named Red River City, up the road from the old Rio Colorado settlement, was established in 1895 after the discovery of gold in the area; that town’s population ballooned to over 2,000 in 1897 (188).

Gold mines such as the Midnight, Anchor, Caribel, Edison, and Memphis mines were close to Questa and were worked in the 1890s; the small, albeit short-lived towns of Midnight and Anchor sprung up at the sites of these mines.Unfortunately, ore had to be sent to Denver for treatment, and this along with legal issues regarding the land on which the mines were located resulted in their abandonment after only a few years of operation. (A) Questa served as a shipping point for many of these placer mines. (Placer mining was done by panning or with sluice boxes, which separated minerals that had washed down from the mountains from the mud of creek beds.) (B)

By the end of the 19th century, mineral deposits were found much closer to Questa; in either the 1880s or 1914 (historical accounts differ), two prospectors found a metallic material in outcrops in Sulphur Gulch, so named because the yellow-colored almagre scars were thought to be sulfur. They are really the natural hydrothermal scars that date back to interglacial periods and are evidence of abundant surface water speeding the dissolution of pyrite, and freeze/thaw cycles destabilizing the rock of this mineral-rich mountain. They did not know what it was but they staked claims anyway, and at some point sent out samples to be assessed.

The beginning of World War I (1914-18) had greatly increased the demand for molybdenum, and assayers were becoming aware of the value of the mineral molybdenite. When an assayer returned a report to these prospectors, he mentioned the presence of molybdenite and its value.

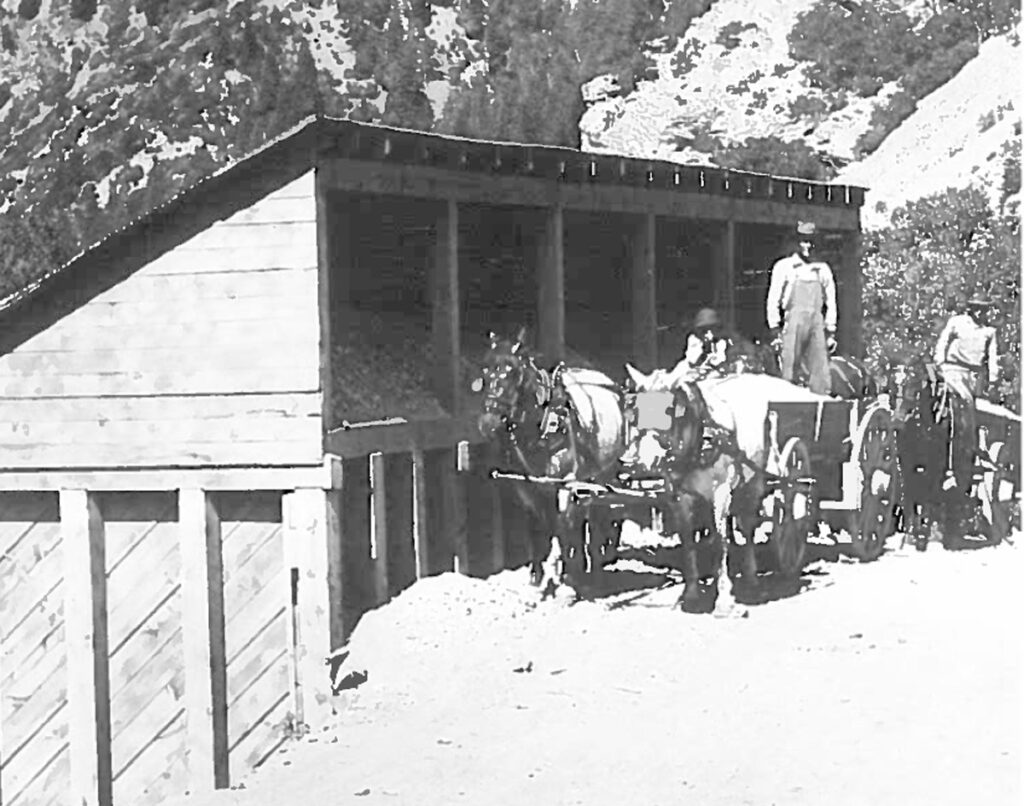

Locals and farmers knew of the chalky grey-black substance further north up the river and mistook it for graphite: they mixed it with grease and lubricated their wagon wheels. It also served as a shiny shoe polish which, unfortunately, rubbed off on everything.

Do you have specific mine-related stories to share? QuestaStories.com is an archive for your contributions, and you can also contact me, Martha Shepp, at QuestaDelRioNews@gmail.com. I dearly want to draw upon real people and real stories by way of illustrating what makes Questa what it was, what it is, and what it can become.

RESOURCES

Chevron. “Life after Mining: Helping Questa Find a New Future.” Chevron.com, Chevron, 1 Jan. 2017, https://www.chevron.com/stories/life-after-mining and https://www.chevron.com/stories/solar

Amigos Bravos, https://amigosbravos.org/chevron-questa-mine

Association, IMOA International Molybdenum. Molybdenum History, http://www.imoa.info/molybdenum/molybdenum-history.php.

Author unknown, “Well, Hello Moly!” Sept.- Oct., 1983, Seventy Six magazine, pp. 1-11. “Chevron Questa Mine Site Profile.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 20 Oct. 2017, https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanup&id=0600806#bkground.

Coté, Claire, www.nmwild.org, Vol. 9, Number 1, Winter 2012, New Mexico Wild! The newsletter of the New Mexico Wilderness Alliance, “Chevron Questa ‘Moly’Mine Views and News, pp. 17-18. Used with permission.

Mine and Concentration Plant: Red River, New Mexico. Brochure published in 1926 by the Molybdenum Corporation of America, Pittsburgh, PA.

Ortega, Tessie Rael de, and Cuddihy, Judith. Another Time in This Place: Historia, Cultura y Vida en Questa. Privately published, 2003. Used with permission. Also A. and B.

Sherman, James E. and Barbara H. Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico. Univesity of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1975.

U.S. Forest Service—Carson National Forest, USDA. Placer Creek mining history trail; Pioneer Canyon trail, mining history of Red River.

Red River Public Library and Historical Society Archives, as follows, thanks to Holly Fagan

• John H Schilling, Geology of the Questa Molybdenum Mine Area, Taos Co. NM, State bureau of mines and mineral resources, NM Institute of mining and Technology, Bulletin 51, 1956.

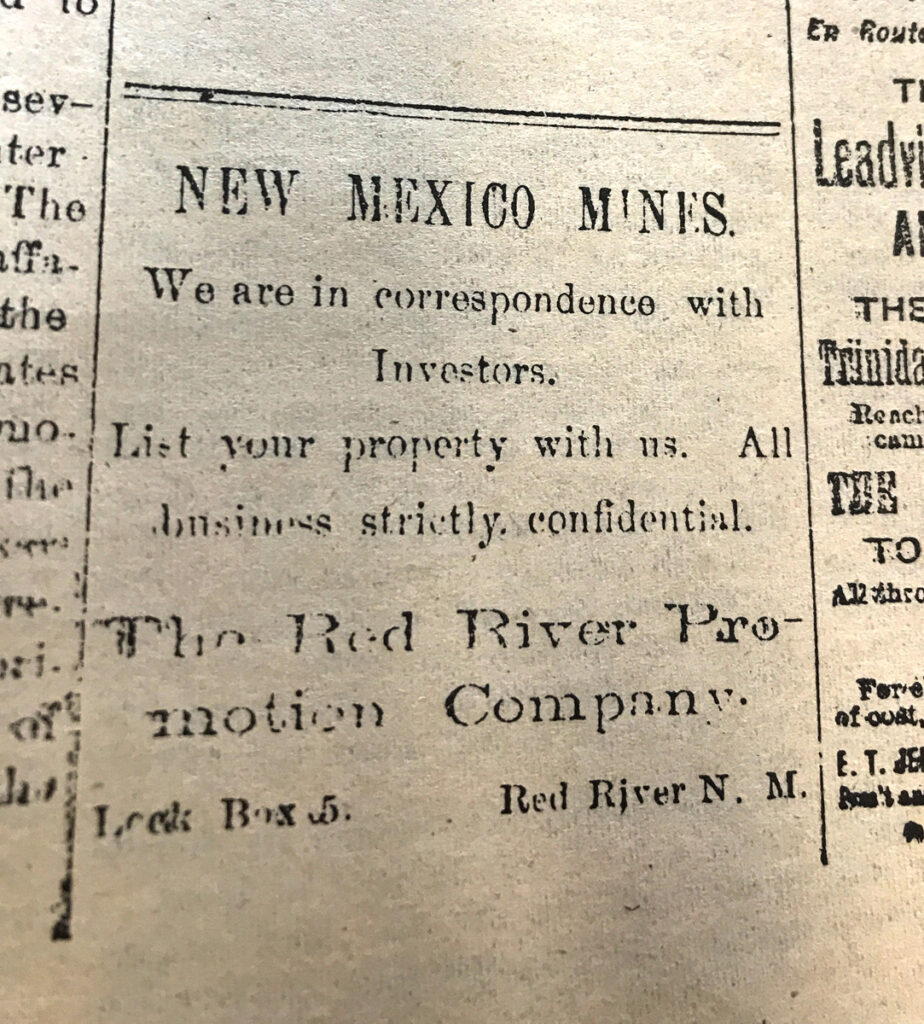

• Red River Prospector newspaper clipping, December 15, 1900.

Wikipedia

Author

-

Questa Creative Council Board member and artist: Martha Shepp preaches the gospel of the power of creativity. One of her loves is to collaborate with open-minded genre-free artists like Mark Dudrow, playing life-affirming works that can’t help but spark the innate creativity of listeners like you. Her expressions also take form with words, choreography, and visual art... with ever expanding mashups of all the above.

View all posts