The Republic of Texas made big claims about owning eastern New Mexico. Their one attempt to assert authority across the Plains ended in embarrassment.

The year is 1841 and The Republic of Texas is struggling mightily. The nascent country was still disputed territory. While the United States, Great Britain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands recognized Texas’s sovereignty, the other European powers did not and neither did Mexico, the country from which Texas claimed its independence. The new nation of Texas’s economy, a cut-and-paste version of the commodity-based slave system of the U.S. South, was suffering. Cotton was the republic’s only major export and prices had fallen significantly. Since hitting an all-time high of 22¢ per pound (about $144 in 2022 dollars) in 1836, the year of Texas independence, the price had fallen to 8¢ per pound in 1840 ($52.50 today).

The Texas government had staked the nation’s future on increasing cotton profits, which would drive further economic development. What’s more, the government owed nearly $10 million ($6.5 billion in 2022), mostly for services rendered during the Texas Revolution. Broke and desperate to find a new source of income, Texas president Mirabeau B. Lamar hatched a scheme to fill the government’s coffers and make good on a long-standing land claim.

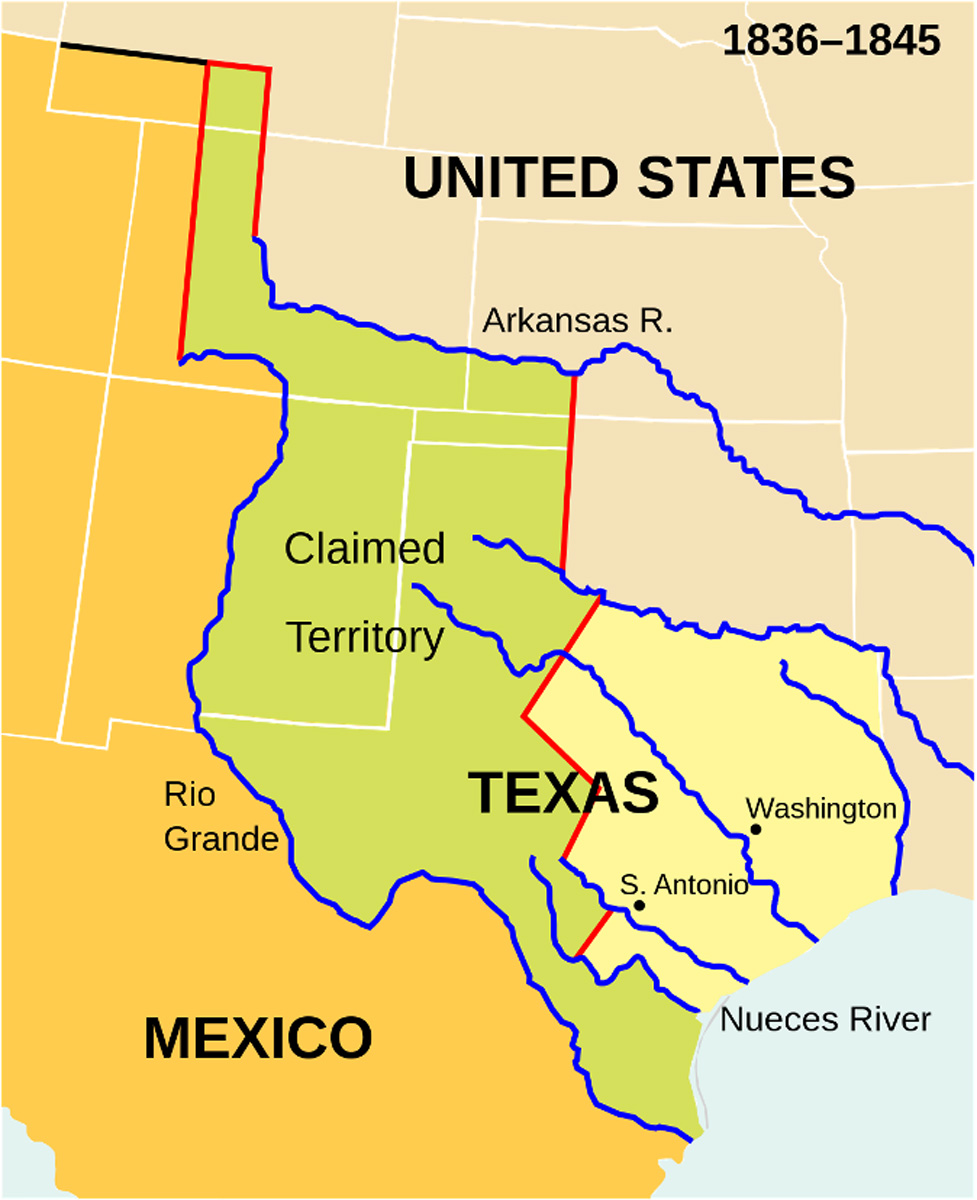

Texas claimed that the Treaty of Velasco, which ended the Texas Revolution, gave the Republic all of Mexico’s lands on the left bank of the Rio Grande and its headwaters, all the way into modern Wyoming. This included most of New Mexico as well. Mexico said the treaty was invalid since it had been signed under duress by Mexican president Santa Ana, who was a prisoner of Sam Houston’s army at the time.

As far as Mexico was concerned, Texas was merely a province in rebellion, one taken over by Anglo-Americans who had contravened their agreement to settle in Mexico by keeping people in slavery and by refusing to convert to Catholicism as they had promised. To them, Texas ended at the Nueces River and at a line roughly west of today’s I-35 corridor and it always had. In reality, the Republic of Texas controlled this area, and just barely. The southern border was lawless, and the western frontier always disputed with the fierce Comanche.

President Lamar decided that if Texas could take control of the trade along the Santa Fe Trail, a trade growing by the month, the profits would be enormous, enough to pay the government’s debt in time. There was also a belief that New Mexico’s growing dependence on trade with the United States and its taste for US goods might mean significant support among the New Mexican population for joining the Republic of Texas. Lamar decided to send a mission west through the uncharted plains, ostensibly to establish trade relations with Nuevo México. But in addition to merchants, Lamar planned to send a detachment of troops, just in case the opportunity to seize the Mexican state for the Republic of Texas might present itself (which he expected it would). The whole operation was to be unofficial, of course. Just a group of traders, with a small force to defend from Indian raids, finding a new way to Santa Fe.

When Lamar’s plan failed to get approval from the Texas Congress, he decided to act on his own. On June 19, 1841, over 120 traders with 21 oxcarts loaded with $200,000 in goods set out from Fort Kenney north of Austin for Santa Fe, along with at least 200 soldiers.

The ill-fated journey went badly from the start. The one Mexican guide that the party was depending upon abandoned them in less than a month. Poor planning led to a lack of supplies since the party had expected to largely live off the land. Water was scarce, as it still is. A series of Indian raids depleted both food and munitions. Lost, the leaders were forced to send an advance party to scout the way. The scouts reached New Mexico on Sept. 12. They were met by local traders who sent news of their arrival.

Expecting a warm welcome from the locals, the Texans were shocked when, on Sept. 17, they were instead met by 1,500 members of the Mexican Army, including Taos and other Puebloans who were pressed into service, under the command of Santa Fe native, Donaciano Vigil. The exhausted Texans surrendered. The next morning, New Mexico governor Manuel Armijo arrived with more troops. He wanted all the Texans summarily executed and put it to vote by his officers. The majority decide to spare their lives but that did not mean release for the Texans. They were forced to lead the Mexicans to the main group and on Oct. 5, the rest of the Texans were captured without a shot.

The whole party of Texans was then force-marched 2,000 miles to Mexico City on starvation rations to stand trial, during which many died of fatigue and disease. Beatings by the Mexican soldier certainly contributed as well. The survivors were then imprisoned in Veracruz until diplomatic efforts by the United States secured their release.

While in Mexico, the Texans were seen as interlopers, at best, and criminal invaders, at worst. In the United States, many were sympathetic to the Texans, who were almost all American-born. Many Americans saw them as wayward and adventurous Sons of Liberty who were fulfilling America’s Manifest Destiny to spread the Anglo-Saxon race and its institutions across the continent.

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition doomed the presidency of Mirabeau Lamar. Unable to stabilize their economy, the Republic of Texas asked to join the United States in 1845 and was granted statehood. After the conclusion of the Mexican American War in 1848 and the transfer of Mexico’s northern half to the United States, Texas surrendered most of its claims on New Mexico in exchange for the U.S. government assuming Texas’ massive debt.

So, remember, if you hear a Texan brag about how their state used to “own” most of New Mexico, you can smile knowing just how wrong they are.