Clay Allison was a fiery man, a man of justice. When he heard who the judge would be, a magistrate known far and wide for his corruption, Allison knew that justice would not be served, he knew a killer would walk free. And not just any killer, but a monster who had murdered his own child to cover up his other killings; a monster named Charles Kennedy. Allison and his brother John began gathering a mob to ride on the jail and see that the monster got what he deserved…

It all began a couple of months earlier when a badly beaten Ute woman fell through the doors of an Elizabethtown saloon where Clay Allison and his friend Davy Crockett (nephew of the Alamo defender) had been drinking. The woman told the gathered patrons a harrowing story; her husband, a white man, was a killer. He had murdered numerous travelers at a guest house he ran at the base of Palo Flechado Pass, on the road to Taos. Once lured in, he would murder them in the most cowardly of ways – in their sleep or while they ran away, unarmed and begging for their lives — just to relieve them of their property. She hated him but she was terrified, her fear was reinforced by daily beatings.

Earlier in the day, a lone traveler (an Easterner, many believe) stopped at Kennedy’s house for a meal. Commenting on the race of Kennedy’s wife and son, the man casually asked if there were many Indians in these parts. Kennedy’s 9-year-old son responded, saying “Can’t you smell the one papa put under the floor?” Enraged, Kennedy killed the man and then turned on his own son, bashing the child’s head in with a fireplace poker. He then beat his wife bloody, locked her in the house and proceeded to get blindingly drunk outside. After he finally passed out, she escaped and walked barefoot to Elizabethtown in a storm.

Allison, Crockett and a posse of other E-town men set off at once for the cabin, where they found the drunken Kennedy still passed out. They bound him and searched the place, finding the bodies and bones of his many victims. They took Kennedy back to Elizabethtown and handed him over to the law.

But while the shocked community awaited the trial, news came that a corrupt judge would be working the case, a man opened to bribery. Allison knew Kennedy would have no problem affording the bribe and sprang into action. He and his brother John gathered a lynch mob and took Kennedy from the jail at gunpoint. Before they strung him up, Kennedy is said to have confessed to killing 21 men. Rather than find a tree for hanging, Allison drug the gasping and struggling killer behind his horse, not just until dead, but until Kennedy’s head was ripped from his corpse. Allison then took the severed head to Cimarron and put it on a stake in front of the St. James Hotel so that everyone would know what fate befalls a mass murderer when Clay Allison is around. It would be one of many violent exploits in the life of the so-called “gentleman gunfighter.”

At least, that’s how the story’s told. Or one version of it, anyway. There are almost as many versions as there are storytellers. But what really happened and who was this killer?

What do we know?

The first public record that can be definitively linked to Kennedy is his marriage to Gregoria Cortes on February 28, 1867. Performed at Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Catholic Church in Taos, it lists “Charles Canady,” as the son of William and Fanny and a native of Tennessee. Gregoria Cortes is described as the only daughter of widower José Cortes of Cordillera de Ranchos and his late wife Antonia Lucero.

Kennedy next appears in an article from the July 4, 1868 issue of the “Santa Fe Weekly Gazette.” The article describes the correspondent’s trip through the region to see the mining camps, where along the way he stops at a stage coach station run out of Charles Kennedy’s home. Coincidently, or perhaps not, one of the writer’s traveling companions who had gone ahead of the others was found murdered some two miles up the trail from Kennedy’s home. The writer, however, was quick to blame the incident on Jicarilla Apache men.

Kennedy is recorded on the 1870 census as a resident of the newly formed Colfax County. It lists the 31-year-old Kennedy as a carpenter, his wife, 17-years old, as an illiterate housekeeper, and the presence of a 1-year-old son, Samuel.

Finally, there’s the article on his demise. The October 13, 1870 issue of the “Santa Fe New Mexican” tells the tale:

Charles Kennedy… was arrested last month and taken to Elizabethtown for examination on a charge of murder. The trial came off… when Jose Cortez (Kennedy’s father-in-law) testified as follow [sic]: That he was at Kennedy’s house on Christmas of last year… A stranger came to the house afoot and stopped for the night; he was an American and had large red whiskers; witness and stranger had gone to bed and witness was asleep when a pistol shot awakened him; there was no light in the room but Kennedy soon after lit a candle, and witness saw the stranger lying dead on the bed with a bullet hole through the head… after refusing to help Kennedy bury the dead man, witness ran away to Taos…

It goes on to tell of how bones found in Kennedy’s garden were examined by doctors who could not say definitively whether they were human. During the hearing, a Taos Pueblo man testified that there was a body buried in one of the rooms of Kennedy’s house and a party went to recover it. A justice of the peace determined the victim was the man José Cortes saw Kennedy murder. Kennedy was bound over for trial and held in a guarded log cabin as Sheriff Houx prepared a more secure jail to keep him through the winter.

Records show that juries were hard to assemble in the early years of Colfax County. Mobs, it seems, were a different story. On Oct. 6, 1870, a mob arrived where Kennedy was held, intent on seeing justice served. They decide to hold an impromptu trial on the spot with Kennedy allowed to pick the jury. The jury couldn’t agree and it was decided to leave him in the hands of the law to face a regular trial.

At 11pm the next night, another mob of around 25 masked and armed men overwhelmed the guards and took Kennedy from the prison. When his body was discovered the next day, the medical examiner determined he had died by hanging. He was buried alone with a wooden marker branding him a killer. (The marker was looted sometime after 2017.)

What happened to his family?

Gregoria disappears into history. It’s likely she remarried, though records have proved elusive. The fate of Kennedy’s son is equally mysterious. If Kennedy had killed the infant, as some versions claim, it would have made it into the news, since that sort of gruesome story is exactly what sold (and sells) papers. It’s possible that if Gregoria remarried that Samuel was given a new name. Considering what Kennedy had done though, it’s also possible the child may have been left with an orphanage.

What was Clay Allison’s involvment?

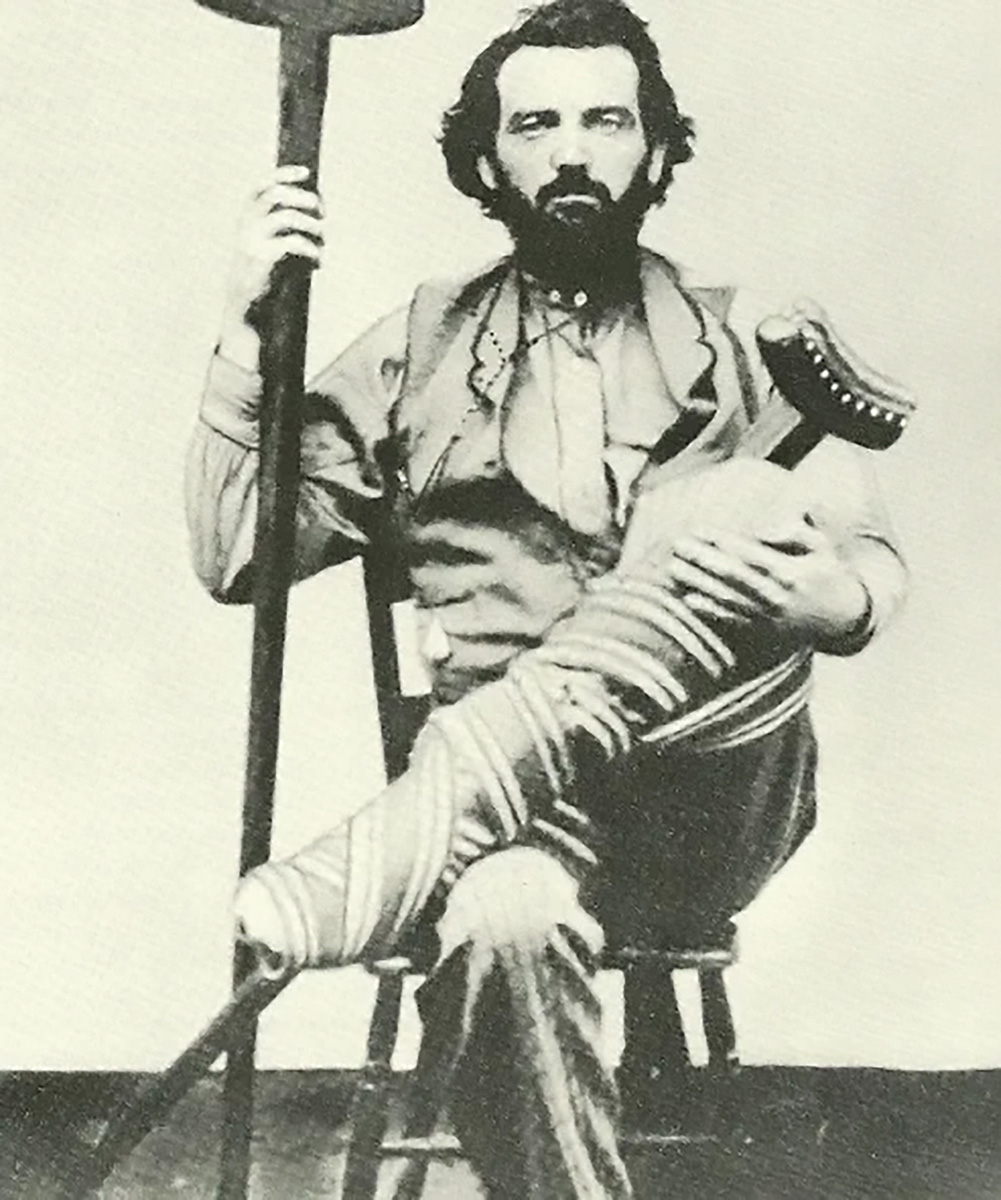

Unknown. Though a fight he had with a group of Apache in Kansas in 1868 had made the local papers, Clay Allison’s fame really came during the Colfax County Wars later in the 1870s. While it’s possible he helped lynch Kennedy, he would have been masked and anonymous like the rest of the mob. He certainly didn’t drag Kennedy though the streets of Elizabethtown or put his decapitated head on a pole, since that too would have sold papers from coast to coast. Plus, no serious biographer of Allison believes he was involved. Most believe he was just trying to settle down and start a new life after the horrors of the Civil War. Allison’s involvement was likely an embellishment by later storytellers, something to give the story more flavor.

How many did Charles Kennedy actually kill?

It can’t be said with any certainty, but many criminologists estimate between 5-15 during his time at Palo Flechado based on his M.O. and length of residency. They believe Kennedy killed for profit primarily and coldly, without remorse. Court records are gone, but local lore says Kennedy was involved in multiple lawsuits with people he’d cheated when his father-in-law finally turned him in for murder. As no record of him before 1867 has been located, it’s possible Charles Kennedy was an assumed name and that he had been killing under a different name before. All we can say for certain is that a brutal man met a brutal end all those years ago.