Southwest Contemporary

Jetsonorama’s Unsilenced installation at the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center dismantles the settler-colonial narrative in the San Luis Valley and amplifies the history of Native enslavement in southern Colorado.

In 2018, the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center de-installed an exhibition about Kit Carson, who is often anointed as a westward expansion hero, but at the brutal expense of Native American people. It had hung inside of the space, located in southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley, for a whopping 68 years.

Today, the History of Colorado’s Borderlands of Southern Colorado initiative is moving away from settler-colonial narratives like Carson’s. Instead, the organization is amplifying the histories of the region’s original people (such as Chicano, Indigenous, and Mestizo voices), one that’s sometimes difficult to stomach.

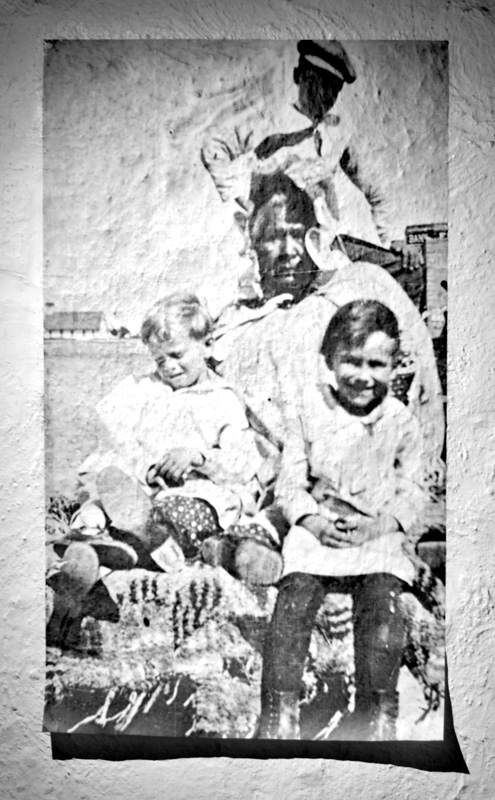

On June 18, 2021, the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center introduced Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado. The site-specific, long-term installation by Chip Thomas (aka jetsonorama)—in collaboration with History Colorado and community members—incorporates photos of Indigenous captives.

Some of the images in the installation, displayed inside of one of Fort Garland’s original adobe buildings (constructed by the United States Army in 1858), are from an 1865 census of enslaved Indigenous people in present-day Conejos and Costilla counties.

President Andrew Johnson, in 1865, had directed Indian agents in the southwest to survey the region to determine who held Native American captives as slaves. According to Thomas, Lafayette Head, a former Colorado lieutenant governor, submitted a list of more than 160 names from Costilla and Conejos counties.

However, Thomas explains, Head’s original submission to Washington D.C. didn’t include the disclosure of Native youth living at Head’s compound or with other families in the town of Conejos. “I thought it would be especially poignant to include a list of those people on the place where the enslaved people were,” says Thomas, a wheatpaste artist, photographer, public artist, and activist who gleaned details from the book The Life & Times of Lafayette Head: Early Pioneer of Southwest Colorado. Head was good friends with Kit Carson, who commanded the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo—the ethnic cleansing effort that forced Diné people to walk from their homelands in what is now Arizona, to eastern New Mexico.

As part of Unsilenced, Thomas, a 2018 Kindle Project gift recipient, reproduced the original list, written in Head’s ornate penmanship, on the side of the crumbling but still standing Conejos County dwelling where the captives lived. The component at the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center displays historical photos, which pose behind a see-through hanging curtain that also shows a reproduction of Head’s slave manifest.

Thomas said the installation, a co-commission between History Colorado and M12 Studio as part of the Landlines project, only moved forward after close consultations with San Luis Valley descendants, historian Estevan Rael-Gálvez, professor and thought leader Ronald Rael, Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center director Eric Carpio, and many others. “The Fort Garland people wanted to de-center the settler-colonial narrative and center the Native narrative,” says Thomas Carpio, who is also the chief community museum officer at History Colorado, a nonprofit division of the Colorado Department of Higher Education, says that Thomas’s piece is a public-facing start to decolonizing thought in the region. “The vision initially was to tell a fuller, richer, and more complex history of southern Colorado,” says Carpio (Chicano/Mestizo). “In a lot of ways, southern Colorado is very different historically and culturally than the rest of the state.”

“We see Chip’s installation as a way to more publicly engage and create public awareness,” Carpio says. “We hope it will transform into broader and deeper dialogue and understanding. This is a history that’s really complex and nuanced.”

Thomas, a Black artist and physician originally from North Carolina, who has lived and worked on the Navajo Nation for thirty-four years, is sensitive to the fact that a Black artist is telling an Indigenous story. “I really tried to approach it from the perspective of Native people, but I’m not Native,” Thomas says. “One question is, ‘Am I appropriating culture and benefiting from it in some way?’ Monetarily, I am not. It’s been an ongoing question since 2009,” when Thomas started The Painted Desert, a public-art mural project on the Navajo Nation.

“It warmed my heart to hear that several Native people left positive comments about the exhibition at Fort Garland,” Thomas says. “They felt welcomed in that space when they didn’t necessarily feel welcome before,” when the Kit Carson exhibition was on display.

Carpio, of the Fort Garland Museum and History Colorado, says that they plan to work with Native artists and continue in-depth discussions with local stakeholders. Ahead of Unsilenced, History Colorado hosted a series of virtual workshops with descendants, community members, and genealogists. “I think this installation poses a lot of questions that we are ready and willing, as a museum and historical society, to try to uncover and understand,” says Carpio.

Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado is on display at the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center, 29477 Highway 159, Fort Garland. Visitor hours, ticket pricing ($0–5), and more information is available at h-co.org/FortGarland. At press time, the installation didn’t have a closing date.

This story was originally published by Southwest Contemporary July 19, 2021. Reprinted with permission.