By Martha Shepp and many others

This community paper is endeavoring to offer a Questa mine history series over the next few issues, to bring you stories from the earliest discovery of molybdenum right up to the present with the goal to review, freshen up the facts, and celebrate the story of our place. The complexity of interrelated stories, the history as it was lived by human beings; this is part of the mine story, too, and worth telling again… or for the first time.

From Part 1, we left off…

The beginning of World War I (1914-18) had greatly increased the demand for molybdenum, and assayers were becoming aware of the value of the mineral molybdenite. When an assayer returned a report to these prospectors, he mentioned the presence of molybdenite and its value.

Locals and farmers knew of the chalky grey-black substance further north up the river and mistook it for graphite: they mixed it with grease and lubricated their wagon wheels. It also served as a shiny shoe polish which, unfortunately, rubbed off on everything.

Part II

The first claims for mining molybdenum were staked in the Questa area around 1914, at the start of WWI. The Western Molybdenum Company of La Jara, Colorado, was organized but did little to develop the claims. In November 1918, the R and S (Rapp and Savery) Molybdenum Company, of Denver, was formed and mine development work was done throughout the winter of 1918-19; small-scale production began in the spring. Abandoned gold mine tunnels probably gave them starting points in the endeavor. In 1920 the merger of the Electric Furnace Reduction Company and the Western Mining Company formed the MCA (Molybdenum Corporation of America), which acquired R and S. In 1922, the property consisted of about 350 acres.

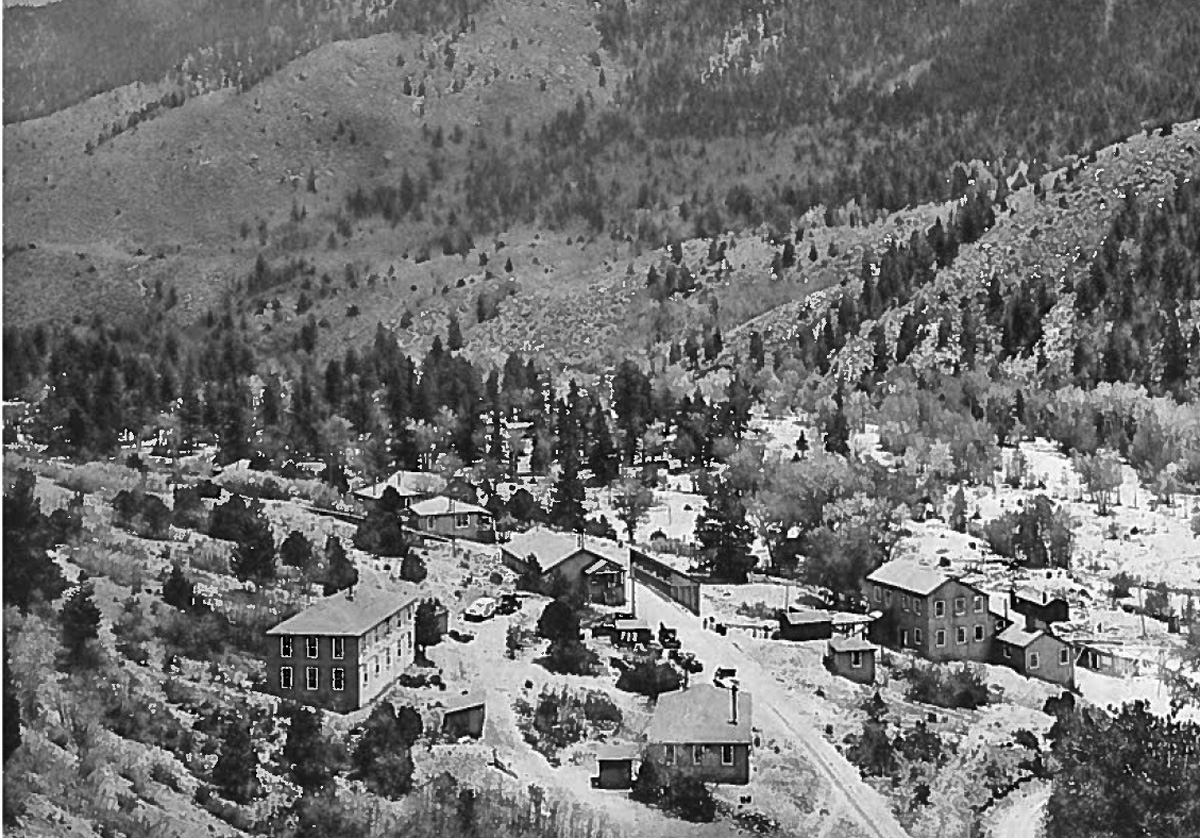

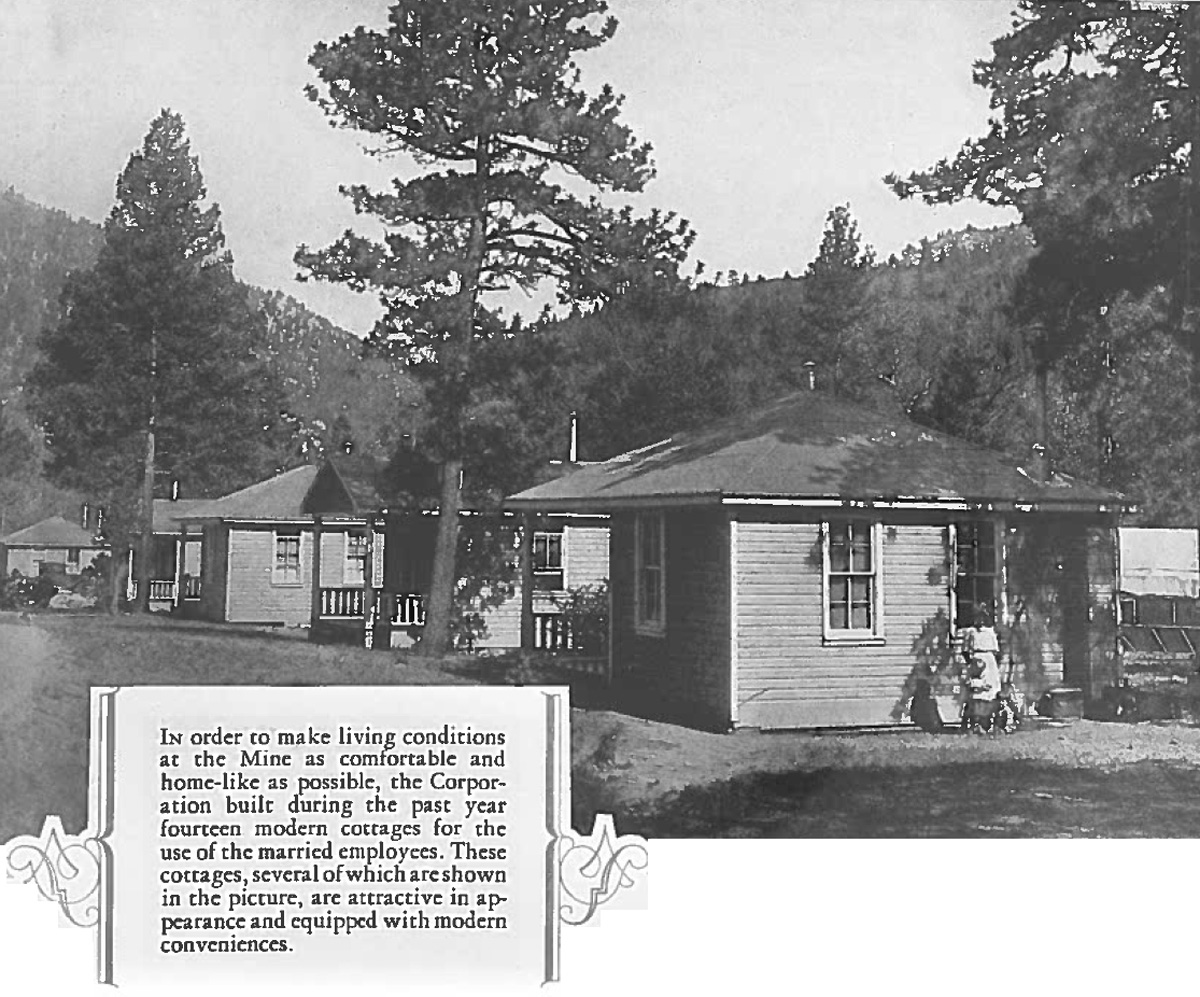

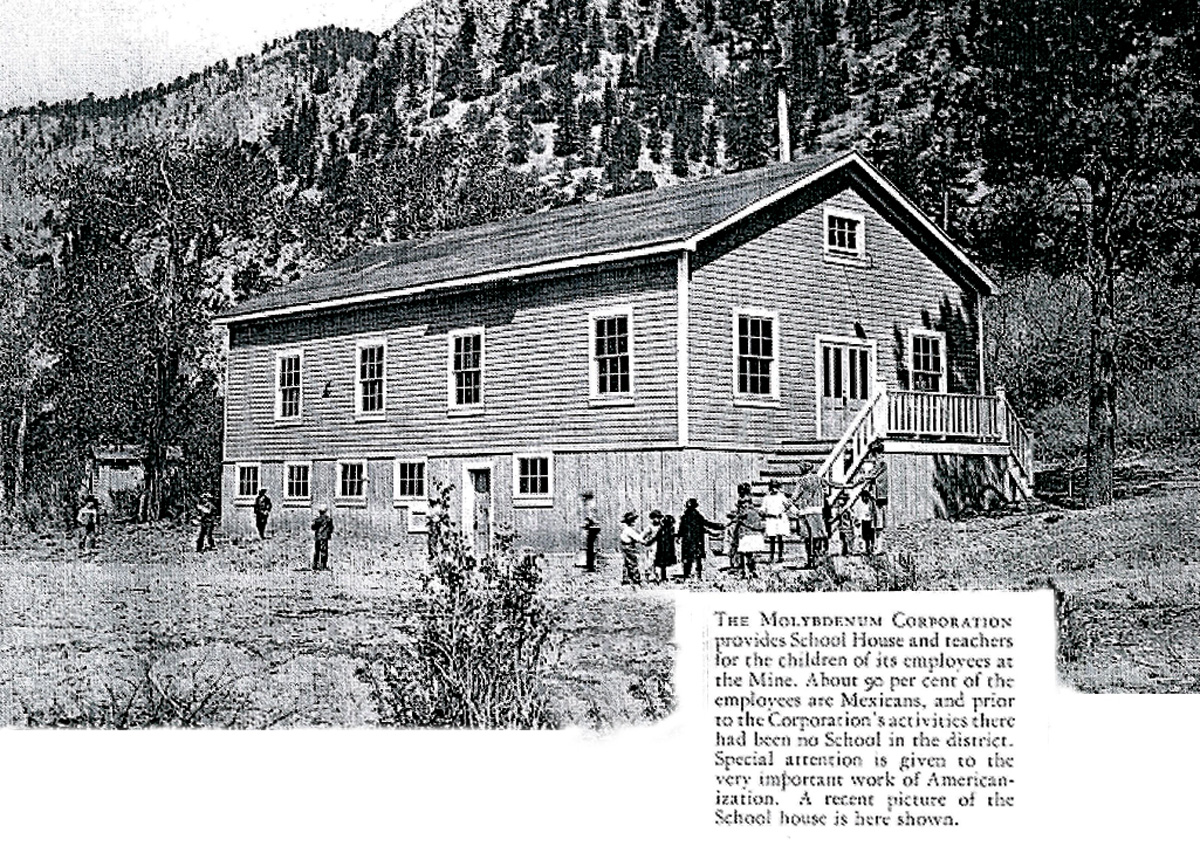

Operations were continued on a small scale until the market vanished in the general depression of 1921, however, a small amount of work to mine high-grade veins was continued and in 1923 a 50-ton-per-day mill and camp were built. This new mill was one of the first flotation mills in North America. The camp included an office, company store, warehouse, mill, assay lab, cookhouse, bunkhouse, 14 workers’ cottages, and a one-room schoolhouse. Previously, miners laboriously loaded ore onto horse-drawn wagons which were lugged uphill several miles to the June Bug Mill, once a gold ore processing facility. Not only was the ore transport slow, the gold mill did not really process the molybdenum well.

Broken ore was loaded into ore cars which were then hauled to the mine portals by mule. There the ore was hand-cobbed and screened to powder, to produce a feed of over 4.0 % molybdenum disulfide (MoS2). Milling was a tedious process. Water was channeled two-thrids of a mile from the Red River to supply water and power to that first Questa mill. (Electricity did not come to the site until 1935.) The molybdenite was then separated from the other minerals by the new flotation process. The concentrate was de-watered, dried, bagged, and shipped to the company’s Pennsylvania roaster, where it was further processed for steel industry use.

What is Molybdenum used for?

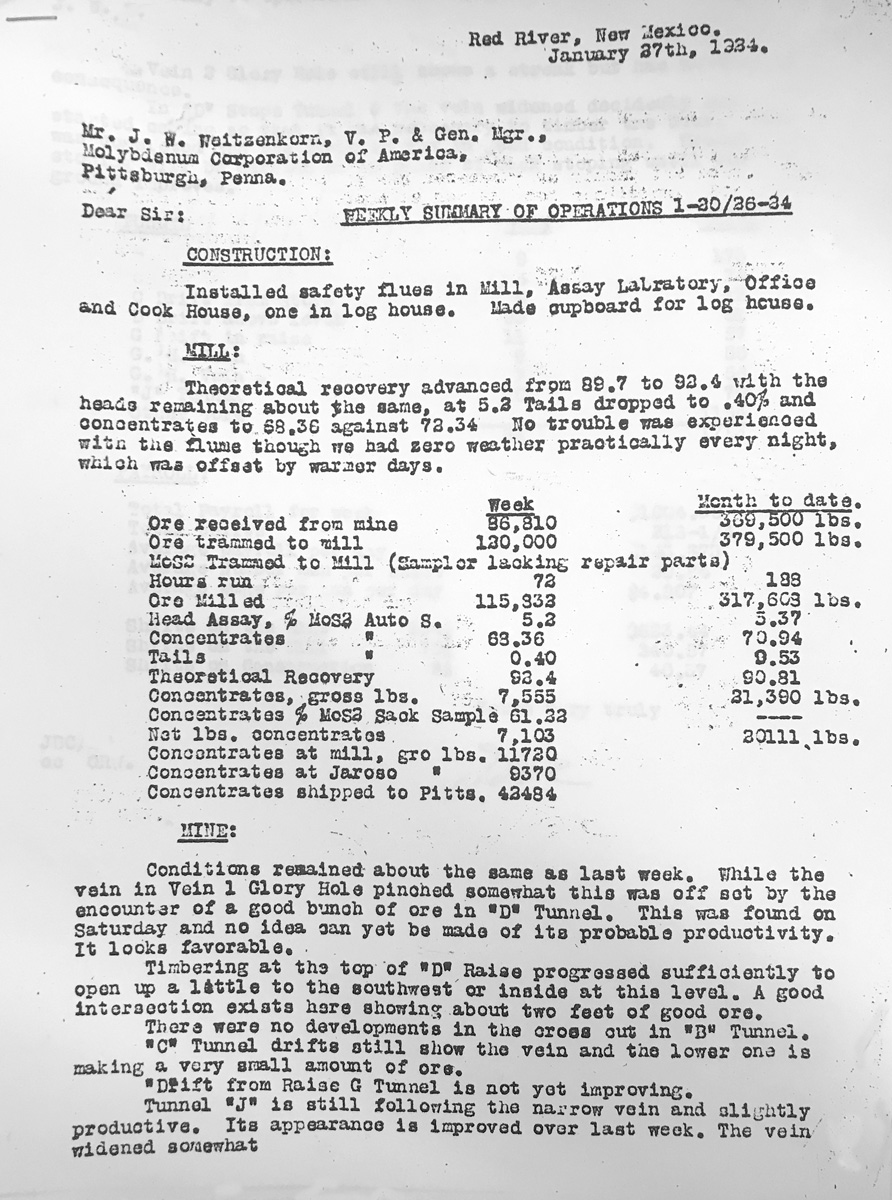

Found in the Red River Historical Society archives, this January 1924 weekly summary document on mine operations was sent to the MCA home office in Pittsburgh.

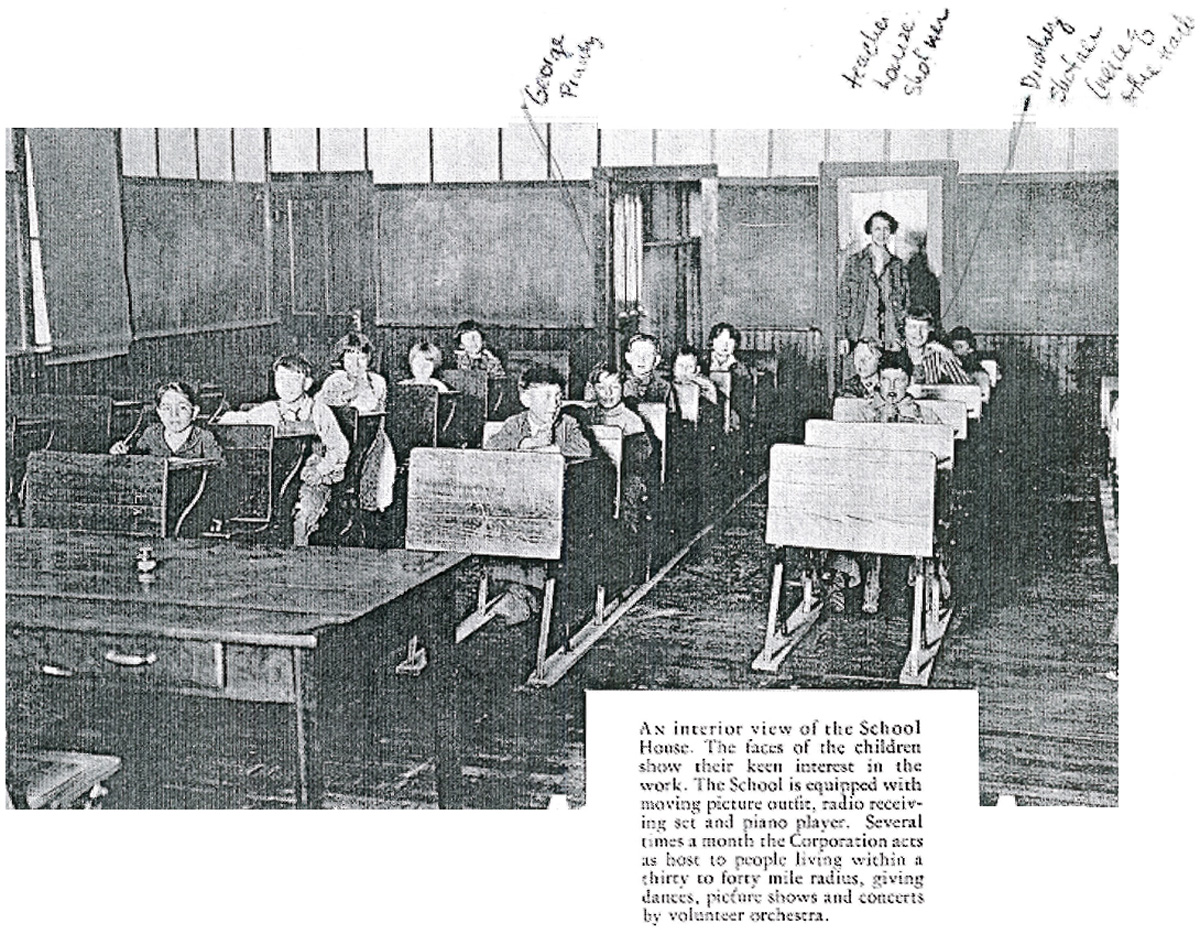

The MCA provides a schoolhouse and teachers for the children of its employees at the mine. About 90% of the employees from Mexico, and prior to the corporation's activities there had been no school in the district. Special attention is given to the very important work of Americanization.

Call outs on this classroom photo may identify some of your great-grandparents?

Although (reportedly) molybdenum was deliberately alloyed with steel in one 14th-century Japanese sword (mfd. ca. 1330), that art was never employed widely and was later lost. In the west, in 1754, Bengt Andersson Qvist examined a sample of molybdenite and determined that it did not contain lead and thus was not galena. By 1778 Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele stated firmly that molybdena was (indeed) neither galena nor graphite but was an ore of a distinct new element, named molybdenum, for the mineral in which it resided, and from which it might be isolated. Peter Jacob Hjelm successfully isolated molybdenum using carbon and linseed oil in 1781.

Through the simple acts of driving a car, cooking with cast iron, or digging in our garden with gardening tools, we are reaping the benefits of molybdenum’s steel-hardening characteristics.

For the next century, molybdenum had no industrial use. It was relatively scarce, the pure metal was difficult to extract, and the necessary techniques of metallurgy were immature. Early molybdenum steel alloys showed great promise of increased hardness, but efforts to manufacture the alloys on a large scale were hampered with inconsistent results, a tendency toward brittleness, and recrystallization. In 1906, William D. Coolidge filed a patent for rendering molybdenum ductile, leading to applications as a heating element for high-temperature furnaces and as a support for tungsten-filament light bulbs. In 1913, Frank E. Elmore developed a froth flotation process to recover molybdenite from ores; flotation remains the primary isolation process. (from Wikipedia)

One can palpably feel the “romance of mining” in the language to describe mining in Questa in the owners’ 1926 MCA brochure.

The introduction reads:

“Every great accomplishment in invention and in industry has been accompanied by adventure; every forward step has been fraught with romance… There is adventure and there is romance in molybdenum. It begins in the high mountains and the deep valleys where the molybdenum is wrested from the earth’s depths, it continues in the tremendously interesting work of floating the little particles of molybdenum up and out of the crushed mass of its mother ore on the backs of little bubbles of air, as well as in the combining of electrically produced heat and carefully balanced chemical reactions to produce the molybdenum products useful to the steel-maker…. This is truly part of the great American adventure, its goal increasing output for each unit of human effort, constantly increasing efficiency and prosperity.”

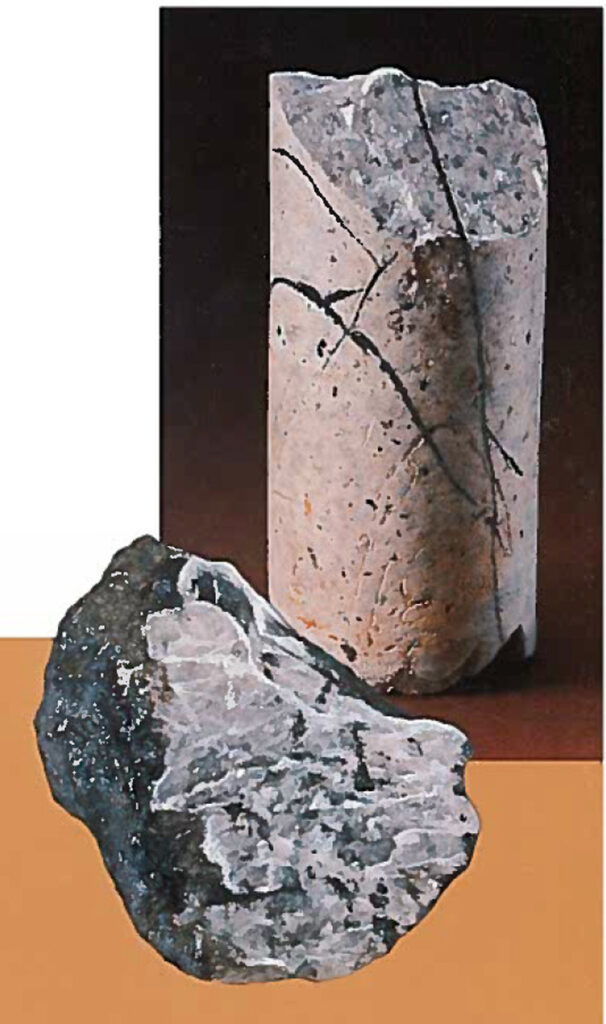

The Questa Mine was unique among the major molybdenum mines of the world because it has produced high-grade molybdenum from fissure veins, in contrast to production from low-grade disseminated deposits at other mines.

In the 1930s, molybdenum’s usage grew beyond its early application for strengthening armor plate and automotive steels into uses for stainless steels, cast irons, and cast steels. With the advent of war in the 1940s and subsequent tungsten shortages, the increased need for high-speed tool steels and ship plate swelled its markets.

To be continued next month…

RESOUCES:

- Chevron. “Life after Mining: Helping Questa Find a New Future.” Chevron.com, Chevron, 1 Jan. 2017, https://www.chevron.com/stories/life-after-mining and https://www.chevron.com/stories/solar

- Amigos Bravos, https://amigosbravos.org/chevron-questa-mine

- Association, IMOA International Molybdenum. Molybdenum History, http://www.imoa.info/molybdenum/molybdenum-history.php.

- Author unknown, “Well, Hello Moly!” Sept.- Oct., 1983, Seventy Six magazine, pp. 1-11.

- “Chevron Questa Mine Site Profile.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 20 Oct. 2017, https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanup&id=0600806#bkground.

- Coté, Claire, www.nmwild.org, Vol. 9, Number 1, Winter 2012, New Mexico Wild! The newsletter of the New Mexico Wilderness Alliance, “Chevron Questa ‘Moly’Mine Views and News, pp. 17-18. Used with permission.

- Mine and Concentration Plant: Red River, New Mexico. Brochure published in 1926 by the Molybdenum Corporation of America, Pittsburgh, PA.

- Ortega, Tessie Rael de, and Cuddihy, Judith. Another Time in This Place: Historia, Cultura y Vida en Questa. Privately published, 2003. Used with permission.

- Red River Public Library and Historical Society Archives, as follows, thanks to Holly Fagan

- Wikipedia

Author

-

Questa Creative Council Board member and artist: Martha Shepp preaches the gospel of the power of creativity. One of her loves is to collaborate with open-minded genre-free artists like Mark Dudrow, playing life-affirming works that can’t help but spark the innate creativity of listeners like you. Her expressions also take form with words, choreography, and visual art... with ever expanding mashups of all the above.

View all posts